The interview: Philip Colbert, on shaking the lobster trap of reality

How death, defiance and democratisation come together in the elusive and cartoonish lobster alter-ego of Philip Colbert.

“There’s a myth that serious structure and rational thought are true. The prison of rules. It’s limiting and false, and the thing I love about Surrealism is that sense of pulling the rug, letting the Other come into play – that sense of shaking the cage of reality.”

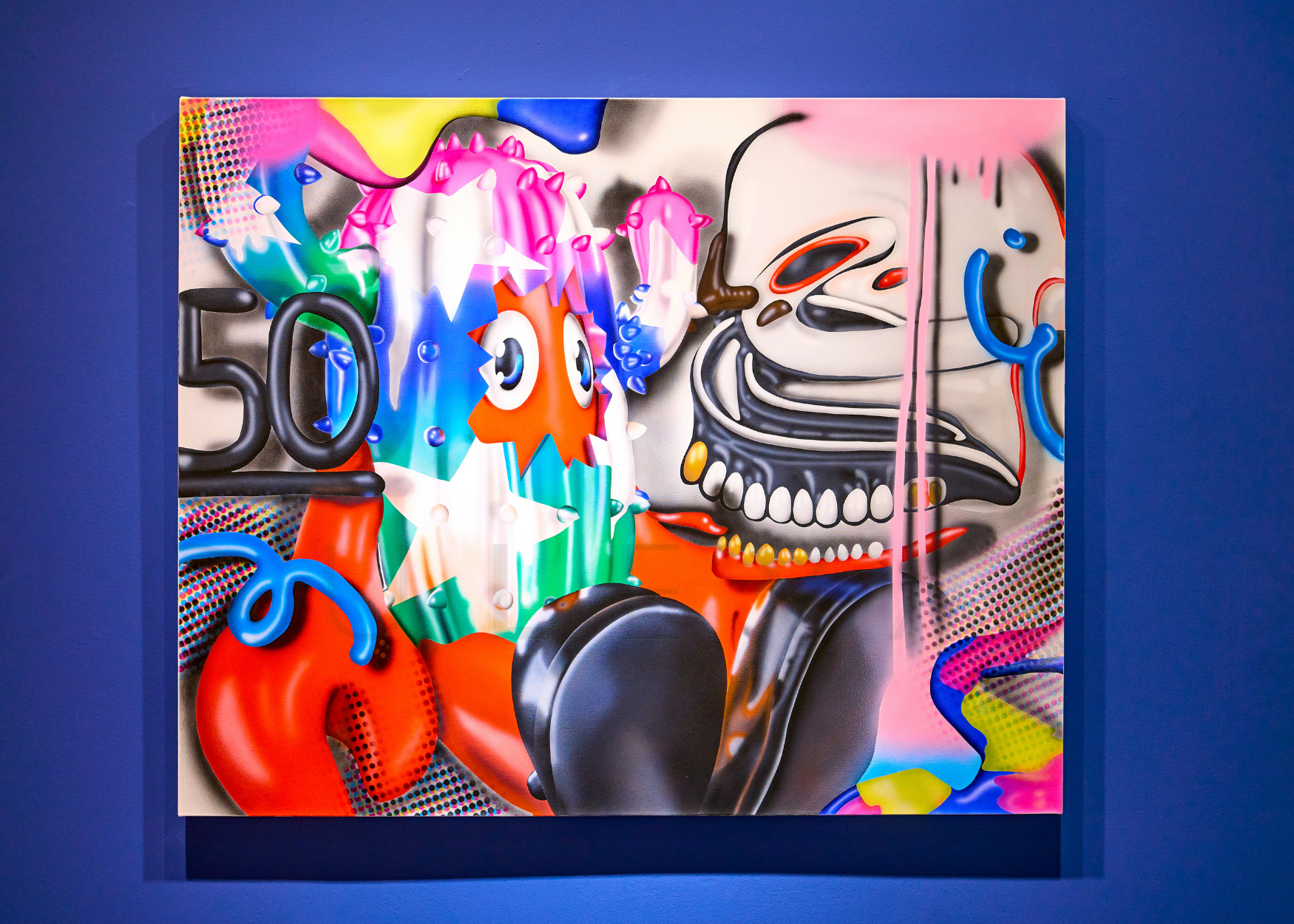

A self-described Neo-Pop Surrealist, Philip Colbert sits in the private showroom at Mucciaccia Gallery in Gillman Barracks, with an intellectual disposition and a lilting, contemplative tone that are largely at odds with his signature streetwear livery of a cap, jacket and t-shirt all emblazoned with his own icons, like a middle-aged baseball die-hard transposed to the world of high art and luxury and satire, complete with cartoon lobsters and fried eggs and a discourse on art and antiquities and metaphysics.

There’s something brazen about his work that risks superficiality – the saturated morass of symbols and emojis and historical references; the shameless Warholian play of brands; the brash colours and ineluctably crass, cartoon lobsters. It radiates from his paintings and especially, for me, from his sculptures, and yet also inflects his speech, this unassuming London chap who looks you in the eye and declares: “I am a lobster.”

There may be a parallel world in which these lobster effigies are not really art, and their creator is one straight-faced, crustacean declaration away from committal. But in this world, we’re sitting in one of the world’s foremost private galleries, Colbert is one of the most celebrated artists of his generation, and we need to remake our reality around Colbert’s art and alter-ego of the lobster. Because, if nothing else, the interview can’t end five minutes in with his impenetrable declaration.

“The very nature of my artistic self, being a lobster, is an ode to Surrealism,” Colbert continues. “By becoming the lobster – my pushing the world of the lobster – this is me pushing Surrealism into the 21st Century.”

And this is how Colbert shakes the cage of our rationalism and our reality. Either we engage with him, preposterously, as a lobster, or we reject the cultural leverage of his art. Which isn’t easy when it stands three-metres high beside Marina Bay, a slash of outrageous colour against the glass and steel architecture of the CBD.

Colbert’s art is all art – a collage of artefacts and Dutch masters and high Pop – and equally a celebration of the everyday: logos and emojis and XX kisses and fried eggs. It marries the play and superficiality of Pop with the disturbing undertow of Surrealism: the red lobster is, after all, cooked – at once hyper-animated and already dead. It taunts our concepts of art and meaning and identity even as it reveres both icon and commodity.

“As with everything in life, there is a great tension at play between democratisation, hyper-stimulation, and sincerity, quality,” says Colbert. “The landscape today is a hyper-Pop state of consumption, on a sci-fi level. On the one hand, there’s a great creative evolution, but on the other, there are dark elements. It’s a complicated battle between forces, and for me it’s interesting trying to capture both elements.”

Frustratingly, it’s as if he doesn’t have a preference – diversion or despair. Democratisation or hierarchy. Even as he pays homage to past masters and appears to enjoy the spoils of his own anointment, Colbert champions the very language of our increasingly mediated, shallow and mechanical interactions. Where is the space for quality and sincerity amidst the saturation of images and the gestural commoditisation of our responses? Where is the space for genuine expression of emotion amidst the LOLs, the XOs, the emojis?

“I use emojis as a motif of the limitations of things in their mass consumption, but also to celebrate them. It’s a duality,” he says. “It’s why I often use the analogy of historical battle paintings; I take that analogy of conflict and apply it to the contemporary mechanics of our value systems.”

But if value is abandoned to these decidedly unresolved contradictions – and the battle painting trope itself is embattled by Colbert’s spray of currency symbols and error messages and likes and logos, and especially by the trident-wielding lobster protagonist – what, then, is quality? Or luxury?

“Luxury is man’s defiance in achieving something beyond,” answers Colbert, in perhaps his least elusive moment of the interview. “The quality of something. The obsession. That can be anything… I was recently in Rome and came upon the Pantheon: the remarkable craftsmanship and design, the scale, the hole in the ceiling. It must have seemed like a spaceship – complete defiance.”

More than play or perturbation, it’s this sense of defiance that takes shape, for me, as the underlying impetus of Colbert’s art. How better to engage with these works – the jarring cartoon figures, the appropriations of Warhol’s appropriations, the contradictory mix of masters and commodities, the preposterous six-metre tall Lobster King sculpture Colbert installed at the ancient gates of Rome, or indeed with his combative proclamation, “I am a lobster” – than in this spirit of provocative resistance.

“The human condition is defiance,” says Colbert. “The contract is death, it’s the one subject of art that is consistent through time. All art pivots around that.”

Even, or especially, lobster art: “The lobster has, as its nemesis, the octopus. I’m thinking of developing more of the octopus in my works, as a symbol of fear, and death. And I like the fact that I am the weaker of the two,” he continues. “And my role – is to defy the octopus.”