Natural pearls become highly sought after as they reclaim former glory

by Karishma Tulsidas

In the history of bad deals, the one between Pierre Cartier and the Plant family likely tops the list. This was in 1916, when pearls were considered the most valuable objects in the world. Cartier had put together two strings of 55 and 73 ‘perfect’ pearls, touting it as their most expensive necklace ever.

At the same time, Maisie and Morton Plant, heirs of the Plant System of railroads, had been looking to sell their mansion on New York’s Fifth Avenue. Cartier had a brilliant idea: he suggested swapping the necklace for the mansion. Unfortunately for the Plants, not too long after, the Japanese unveiled their revolutionary system of cultured pearls, sending the value of those natural pearls crashing down. By the time Maisie passed away in 1956, the value of her million-dollar pearls was just US$150,000.

The Kimberley, a remote and majestic region in Western Australia, where Paspaley sources its most rare and unique pearls.

If these pearls were ever to resurface on the market, we can safely bet they would far surpass their 1956 value. Natural pearls have reclaimed their former glory, and have become highly sought after by collectors and jewellers. Rahul Kadakia, international head of jewellery at Christie’s, says, “Natural pearls have had the greatest following, be it necklaces, finely shaped drops, or fine-quality button pearls. Cultured pearl jewellery tends to do better when incorporated into a jewel with a design element to it.”

Due to over-harvesting in the 1800s, natural pearls were all but wiped out. This inspired Kokichi Mikimoto to develop a system of harvesting oysters on a farm. Essentially, pearls are formed when an impurity (not a grain of sand, as per popular belief) enters the mollusc, resulting in the shell coating the interloper with layers of nacre to protect itself. Mikimoto found a way to artificially inseminate these molluscs, thus leading to the birth of cultured pearls.

While the method of acquisition is different, the pearls themselves, whether natural or cultured, look exactly the same. The only way to distinguish between a natural and cultured pearl, says Rahul, is to use an “x-radiography from a recognised laboratory which can pin-point beads or other materials used for pearl culturing”.

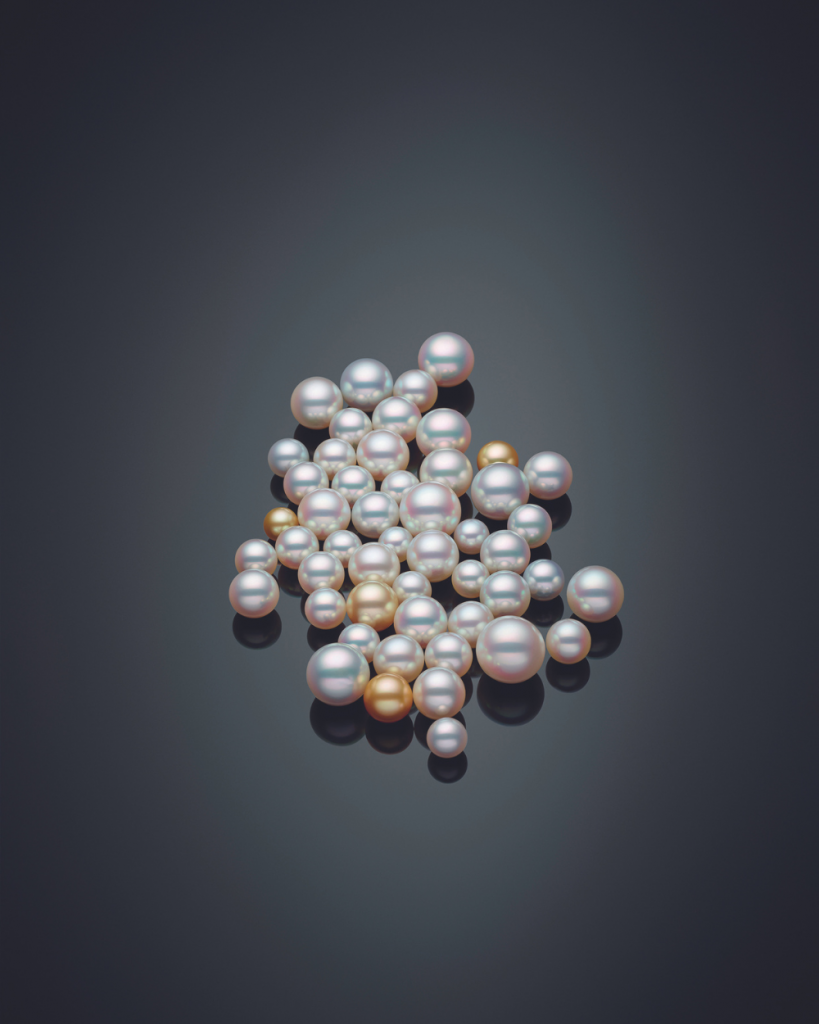

Coveted Paspaley pearls.

Still, cultured pearls are not to be scoffed at. It’s become the predominant way of harvesting oysters, and some varietals command eye-watering prices. One of the most sought-after is undoubtedly the South Sea pearl, found predominantly in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Australia.

Unlike other varietals, it takes about twice the amount of time (two to four years) for a South Sea pearl to develop. In Australia, there are a handful of farms that cultivate pearls, the most famous of them being Paspaley.

The 102-year-old company was founded by Theodosis Paspaley, who moved from Greece to Australia. Highly successful in the beginning, his business started faltering in the 1950s when demand for natural pearls started waning in favour of cultured ones. The company quickly adapted, partnered with Japanese experts, and built a unique system of cultivation. A Paspaley spokesperson explains, “For an Australian South Sea Pearl, these are hand collected by Paspaley divers from the ocean floor, then inseminated by a skilled hand with freshwater Mississippi Clam Shell. Once complete, the oysters are returned to the ocean where they remain for two years developing a pearl. The pearls are then harvested and used in beautiful Paspaley creations – coming from nature, offered in our boutiques in exactly the same way they came out of the ocean.”

Today, the brand has become synonymous with South Sea pearls that form within the Pinctada maxima oyster. In the past century, pearls from Australia have steadily increased in value, as evinced by recent auction results. In 2013, a single natural baroque pearl from Paspaley was sold for US$410,000, while a pair of natural drop earrings went for US$3.53 million in 2014, both at two separate Christie’s auctions.

But why are Australian South Sea pearls so highly sought after? “Australian pearls tend to be larger in sizes due to the warmer water condition as compared to the pearls from Japan,” says Christie’s Rahul. “Australian pearls in fine quality can grow to over 15mm in white, grey, and black tones making them quite desirable. The difference in value is mainly from the sizes, the larger the sizes in fine quality pearls, the more expensive the strand.” When buying South Sea pearls, he advises looking at “size, graduation of the beads, the skin, colour, and lustre.”

Today, Australian South Sea pearls account for only 0.08 per cent of global pearl production, making them ultra-rare and exclusive. Moreover, Rahul adds that it’s becoming harder to cultivate fine-quality pearls these days, due to “water conditions and pollution”.