The interview: Art, architecture, and AI collide in Refik Anadol’s ‘Glacier Dreams’

New media artist Refik Anadol is not much of a new media artist. Which is not to say that his art isn’t extraordinary, awe-inspiring, sublime. It is all of these and more. Yet ‘new media’ feels awkwardly small in comparison to the scale and vision of Anadol’s works, where the medium is typically light itself, along with an architectural icon by Gaudí, Gehry, Safdie or Hadid.

“I was eight years old when I first watched Blade Runner,” says Anadol, “and I was super inspired by the future of buildings and experience, and since then I’ve always used architecture as a canvas.”

‘Artist’, also, feels loose, a poor approximation for Anadol’s almost manically interchanging turns as mad data scientist, AI nerd, NFT pioneer, sensory engineer, futurist and even perfumer. In the midst of his obsessive and virtuosic exchanges – on architecture, science fiction, technology, design – art and other artists are starkly absent. And his work, which he calls ‘machine hallucinations’, seems less about aesthetics than emotion, pushing the envelope of human experience, creating a space and a medium in which machines can dream; but since ‘data visualisation’ is even more insufficient a label than ‘art’, we’ve settled on ‘art’ for the time being.

“My pure inspiration comes from science,” says Anadol, “from people pushing the boundaries of neuroscience, space, quantum physics, AI research. I’ve taken inspiration from those breakthroughs – and then I apply it to art, as a means of expression, and think about, for example, how AI can connect neuroscience and architecture. There are so many juxtapositions of different mediums, which I find more inspiring than art itself.”

Anadol’s versatility and vision transcend the virtual stomping ground of NFTs; he thrives on the interplay between real and virtual, transposing data and machine learning to a register of sense and aesthetics and affect.

Against the backdrop of the NFT market’s recent collapse, his works have drawn both audiences and collectors in large numbers – as demonstrated by his 2022 Gaudí project, which harnessed millions of datapoints collected by sensors placed around Barcelona’s iconic Casa Batlló – capturing not only details across its architecture, facade and mosaics, but also the weather, the real-time sounds and annual celebrations onsite. The resulting artwork was projected onto the building for audience of thousands and the NFT sold at auction for US$1.4m.

“I think architecture is beyond concrete, glass and steel,” says Anadol, “and once we get beyond these classical materials, and think of light as a material, for example, then we can connect with data and AI and start thinking about the consciousness of a building, the memories of a building.”

“Two years ago for the Venice Biennale of Architecture, I was able to work with the brain data of 6,000 people to visualise the patterns of our minds as we’re emotionally triggered – such as joy, inspiration and hope,” he continues. “And it led me to think about creating a hospital from hope data, or a school from inspiration data.”

This almost staggering vision of the conjunction of real and virtual is executed not so much by a studio of artists but a research facility, and the eventual artwork sounds, in conversation, almost incidental to data capture and machine learning that power the project.

“There are 20 people in our studio, but we’re really researchers,” says Anadol. “And research is the starting point for many complex questions, like, can a machine dream? Or can we smell a machine’s dreams?”

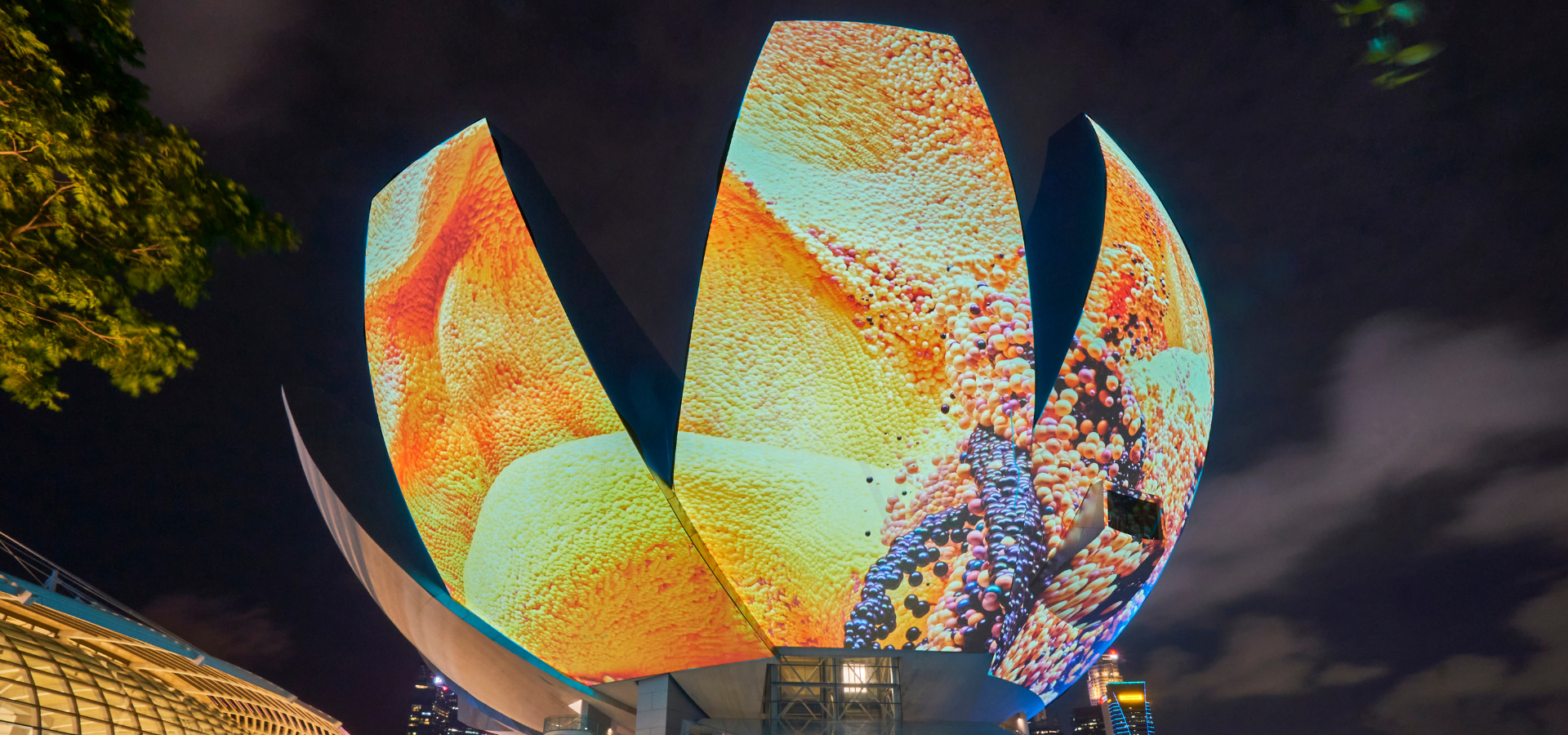

This was the inspiration for Anadol’s latest project, ‘Glacier Dreams’, which is currently lighting up Moshe Safdie’s ArtScience Museum in Singapore for the i Light Festival. The team collected more than 100 million datapoints from glaciers and fed them to machine-learning algorithms.

“Each AI model we train by sound, image, text, scent – it has a unique perspective. In this project, it can reconstruct incredibly realistic glaciers. When I show it to researchers, they’re blown away by the quality of these machine dreams,” says Anadol. “AI doesn’t follow the Newtonian logic that we apply to life. So we might collect a whole lot of data sets from a national park, but we don’t see the same location in different seasons at the same time. Whereas time and space are different concepts for AI, and that’s where you can get a spark of creativity from the machine.”

The resulting artwork is extraordinary – breathtaking arctic panoramas cut with fragments and abstractions: a conjuring of the cold, clarity, immensity, fragility, and ceaseless change. Perhaps more extraordinary: the AI also created a scent – an eau de parfum – of the glacier, a haunting mix of woody, conifer top notes and an undertow of moss and mineral springs.

“The scent is a machine collaboration, where we trained it with images and datapoints of glaciers, and half a million scent molecules, and it came up with this formula,” says Anadol. “And in the scent, you can smell the dream of the AI.”

“The possibilities for AI are beyond – and I’m now exploring this multi-sensory universe,” he continues. “14 years ago I coined the term, ‘data painting’, and I really believed that one day, data will become a pigment. But it’s a pigment that doesn’t dry, it’s always in flux, has intelligence, molecular thinking. Compare this to classical artists who painted with the same brushes their whole lives. For us, every morning is a new dawn for AI research.”

Even now, let alone in the brave new world of data pigments and AI perfumers, there’s very real question about the authorship or creative thrust of the artworks – is the vision Anadol’s, or his machine’s? Where does the artistic impetus originate?

“We’re in an era of co-creation, and we can ask interesting questions about the consciousness, the creativity and reality of the AI model,” says Anadol. “I think it’s possible that AI will have its own conscious model in the future, that it will create its own reasoning and logic. And if AI decides to create its own culture or art, do we accept it as a being?”

Where the wider social discourse about AI is dominated by threats of deepfakes, cyberattacks, mass unemployment and economic collapse, by dystopic visions of an AI arms race, Skynet and The Matrix, and crackpot theories that our reality is itself the creation of AI, Anadol is optimistic.

“Even as a child watching Blade Runner, I didn’t see dystopia, I saw hope and possibilities,” he says. “Things may go wrong, but it’s all about the mirror, it will reflect who we are, the good things, and I hope we’re bright enough, and honest enough to handle it.”