The interview: Singaporean artist Suzann Victor fractures the colonial gaze at her latest exhibition at Gajah Gallery

by Karishma Tulsidas

Photography by Jin Cheng Wong

Over the past three decades, Suzann Victor has held an outsized presence in the Singapore art scene. Her latest solo exhibition at Gajah Gallery, A Thousand Histories, extends her exploration of the themes of colonisation and objectification. Using lenses as her primary medium, Victor reimagines the concepts of seeing and being seen.

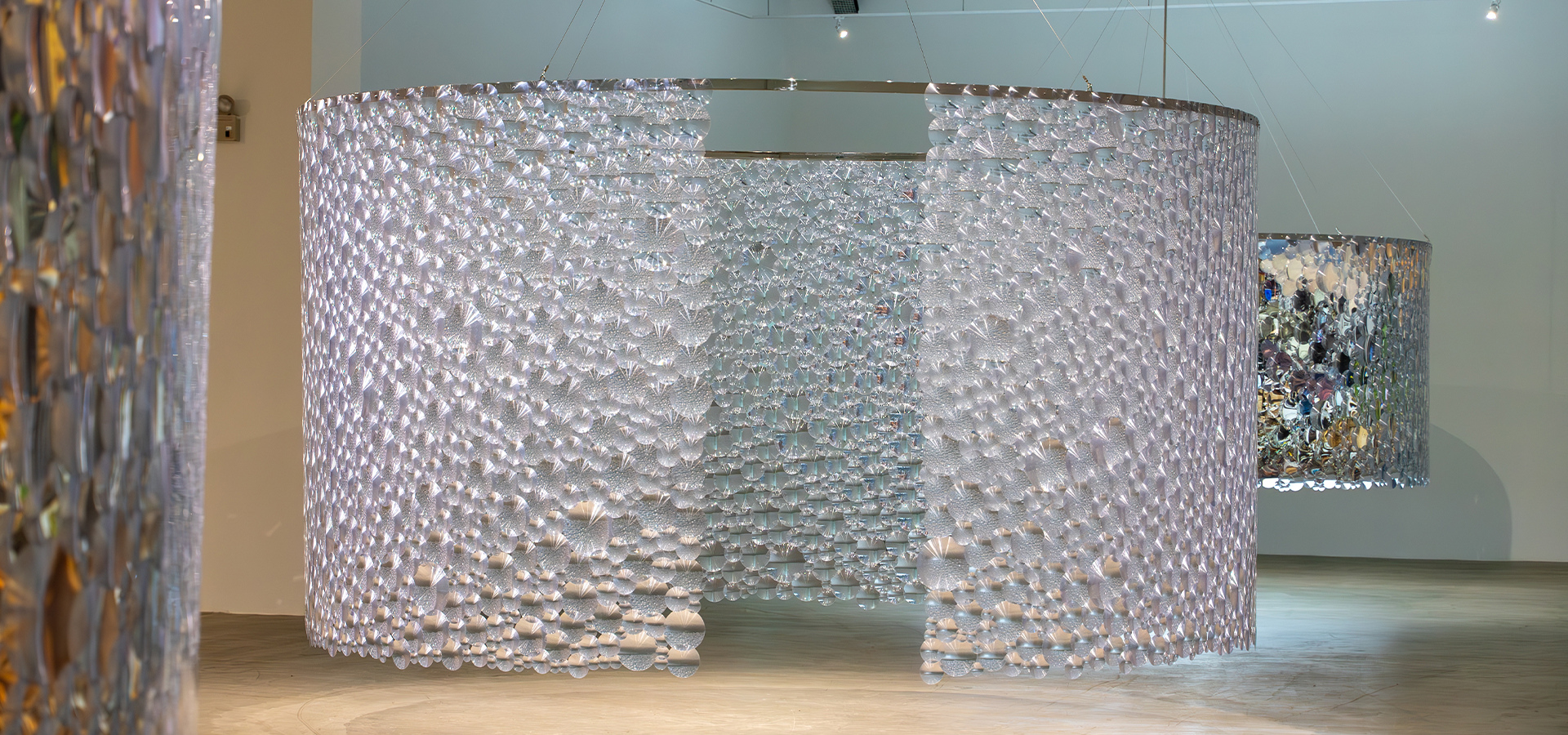

The exhibition features four works, among them City Lantern and Sea Lantern. Both present seamless 10-metre-long collages of colonial-era Southeast Asian images filtered through thousands of lenses. The installations rotate continuously in a clockwise direction, each featuring 4,000 lenses that magnify and fragment a ten-metre narrative behind into miniature film-like images. Victor’s concept, produced by Gajah Gallery’s Art Lab in Yogyakarta, was a technical feat that was six-months in the making. “This kind of lens-kinetic lantern had never been constructed before, and the rotating mechanism from the US was innovatively adapted by the Gajah Team for this exhibition,” she explains.

Suzann Victor at her latest solo exhibition at Gajah Gallery, A Thousand Histories. Top: People’s Lantern.

The result is mesmerising: every lens, photo, magnification, and fragment reveals a surprise—from Sutirah, Indonesia’s first female animal handler grasping an alligator, to a Malay postman, to countless women holding their children.

“One of the aims of these works is to impede the acts of hierarchical looking, and the representation of local peoples by the imperial camera. Rather than allowing these images to remain fixed, history is actually alive,” she says. “It’s counterintuitive, because lenses are supposed to magnify and give you more visual information, but what it does is, it actually fractures the image, but only to displace and obscure them all at the same time.”

Sea Lantern features 4,000 lenses and microfilms.

For Sea Lantern, Victor sourced figures directly from photographs dating back to the 1800s, exploring the lives of Southeast Asia’s sea-faring peoples under colonial rule. “In those photographs, the objectified subject conveyed such shattered worlds—because they’re separated from the contexts of their home, their relationships and their communities,” she says. “The exhibition invites viewers to become aware of the complicitness of spectatorship when we encounter the gaze of the people in the photographs.”

The lenses serve multiple purposes, but at their core, it’s about Victor asking the audience: Do we actually understand our past? How can we engage with our colonial heritage, and our ancestors that lived through it? Their struggles, their challenges, the obliteration of their identity? Do we understand how our colonial past has shaped the way we live today—and with that information, how can we honour our ancestors, our past, not through the lens of the colonisers, but through the actual lives lived?

She asks, her pitch underscoring her passion for the topic: “So to speculate—if colonialism had not occurred, how would we be speaking to each other? What language? What kind of architecture would we have? What kind of culture would we have? While that is a very unknown factor, I think it’s important that we view history as something that’s open-ended, rather than fixed.”

Sea Lantern features a seamless 10m image constructed using colonial images seen through varying lenses.

Through her oeuvres, she’s unearthed overlooked chapters of regional history. For her, revealing such stories is about rewriting the narrative and letting the past be told through the eyes of those who lived it—not just those who write about it. “For example, I realised that there were actually several comfort women’s stations in Singapore, which is a suppressed kind of history,” she says. “If you really want to find out who you are, you need to actually also know where you come from and where you are heading towards.”

Lenses, then, are not just a visual tool—they don’t just clarify or magnify, but also destabilise the visual experience and our own perceptions. “If you were to step back a little bit, you can see in the larger lenses that the image is rotating clockwise. But then if you were to focus your eyes on the smaller ones, you find that the details are going anti-clockwise. So part of the optical illusion is that they go in divergent directions, even though it’s actually physically clockwise. And that’s the disorienting, destabilising, physiological and optical effect of this work.”

Through the lens of time

In City Lantern, the imagery shifts from colonial Southeast Asia to a composite of contemporary cities, infused with ecological anxieties. “The buildings are composed and juxtaposed as an architectural quandary on purpose. The way they’re lined up, they just don’t make sense. They’re huge, but also a kind of compression of architecture. The City Lantern introduces ecological distress that we’re experiencing. The buildings range from across Southeast Asia, not just Singapore. You can even see the rubbish floating on the water’s surface.”

City Lantern features a mishmash of Southeast Asian cities, underpinning the ecological distress they’re undergoing.

“So, rather than allowing these images to remain frozen and fixed, history is actually alive and open-ended. We’re powering our civil imagination by being able to look at them in a very different way. and to know them anew.”

Tracing her journey

The silent thread running through Victor’s works has been an innate ability to turn pain into power. Her journey as an artist has been defined by quiet resilience. When Singapore banned performance art, she and her fellow artists found creative ways to express themselves, sometimes to the dismay of the government.

Even when she enrolled in university as a mature student, she was told by a lecturer that she would never make it. “I think I had a real attraction to materiality even as an art student. Back then, I already had the tendency of questioning creativity, the curiosity and the yearning to do, to not repeat or replicate but to do something that fresh or something that pushes the boundaries. And I think I just silently said to myself [to the teacher], I don’t think you know me,” says the petite, soft-spoken artist, who now shuttles between Australia and Singapore.

When asked whether she was driven by a desire to disrupt, she takes a minute to answer: “The impetus was not really to disrupt or to be gone—but rather to point to domination, not the dominated. And it’s a way of decentralising that, and to bring up a self-seeking, self-serving kind of purpose.”

Lens-scape of Unlearning features five floating panels of optical lenses arranged in a grid, creating an artwork that plays with perception.

That resilience has shaped her practice over the past 40 years. Many still remember her swinging chandeliers in the glass atrium of the National Museum, or the public installations staged through 5th Passage, the artist-run collective she co-founded in the early 1990s to make art accessible to all.

With A Thousand Histories, Victor extends this trajectory—confronting viewers with works that fracture the gaze, refuse fixed narratives, and reimagine history as something alive, unstable, and open to rewriting.

A Thousand Histories was on display at Gajah Gallery until 7th September, 2025.

Read next: