The interview: Michael Anastassiades, London-based designer, on his collaboration with Flos and the magic of illumination

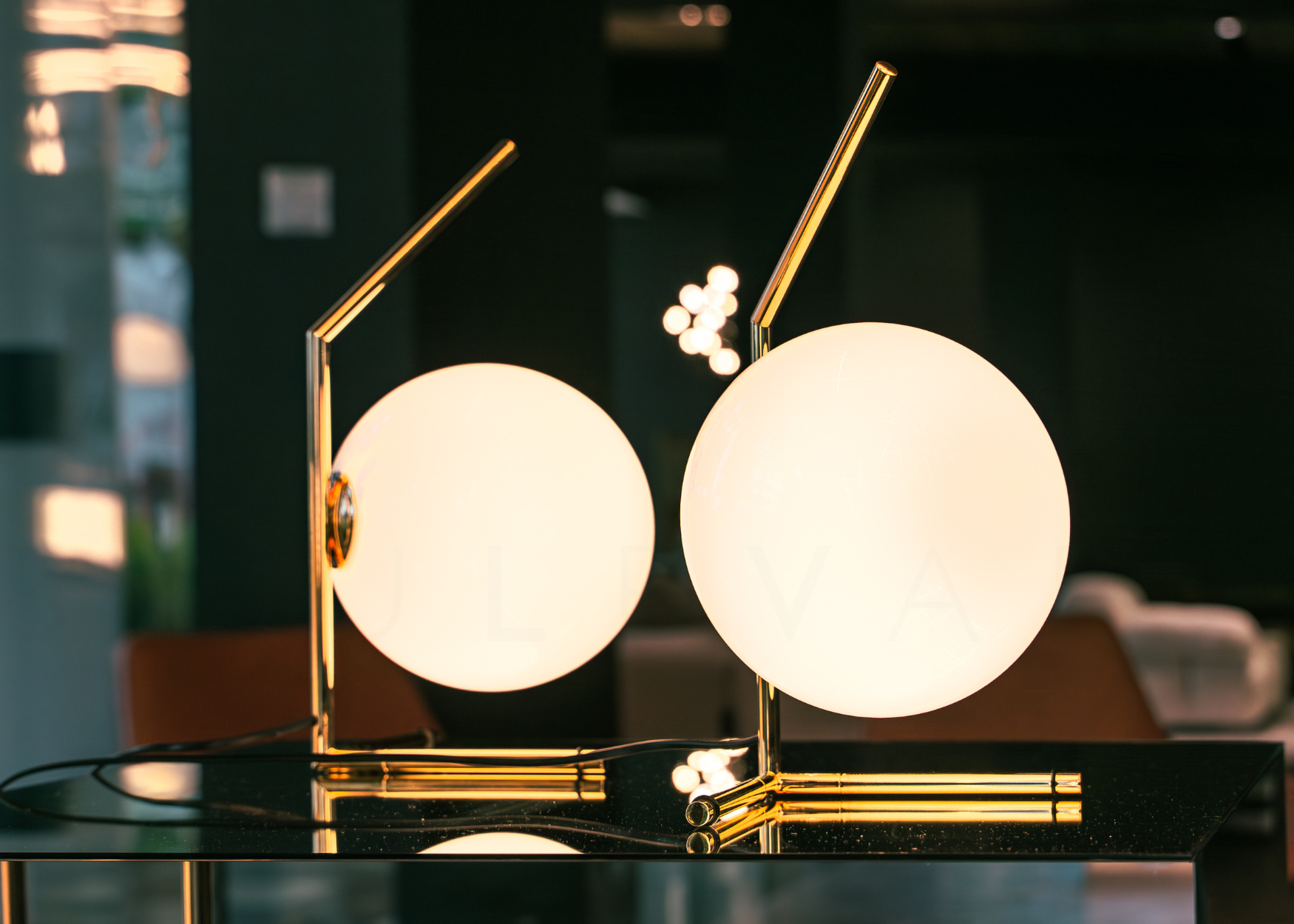

Shot onsite at the Space Furniture showroom in Singapore

Michael Anastassiades, who has blazed a trail in his collaborations with designer lighting house Flos, shares his insights into the art, impact, possibilities and magic of illumination.

Boulevard: Your work pushes the boundaries of design and architecture – how do you balance tradition with innovation?

Anastassiades: Well, I’ve always been a firm believer that there’s nothing really new in the world of creativity. Ideas appear and reappear throughout history. From the moment you accept that, it gets much easier, because you’re not designing from a place of constantly trying to attract attention, but rather, to re-introduce things in a slightly different way that will make it interesting for people to appreciate. The intention is not to shock with something you design; the intention is to approach it from a place of familiarity. I didn’t invent the sphere, and I didn’t create brass as a material; I just introduced it at a time when nobody else was using it, and when they treated brass as an out-of-date kind of material from the ’40s or ’50s. But for me, brass is beautiful – I love the way it reflects light.

So going back to your question about originality and approach, in a sense, it is about layering your design pieces in such a way that you keep discovering things about them as time passes, as well as creating things that are not always obvious from the first contact.

Blvd: What do you feel is the role of design, and the designer, in shaping the potential for spaces through the objects that fill them?

I always feel that the biggest honour in design is when people don’t actually notice something you’ve done. They enter a room and don’t notice what you’ve created; but on their second visit, the novelty of something that initially shocked or wowed them is no longer there, so they start to notice other things in the area. This is when things change and appreciation gradually grows. That’s how you build something that people want to keep for a long period of time – ideally, forever.

Left: ‘Coordinates’ strip-lights system. Right: ‘Overlap’ suspension lamp in resin and steel. Both by Michael Anastassiades.

I think about how something I design fits in all these different contexts, because I’ve seen my work in spacious, super-pure gallery settings, where everything looks amazing. But the challenge is, when you put it in any interior, like baroque, or whatever, it should really work well and not fight with the space’s design.

A long time ago, I got a commission to design some chandeliers for a Greek Orthodox church in London. We went through a long process of creating these pieces, and I believe they chose me because I proposed a modern design – even though it was a heritage building. The chandeliers were three-and-a-half metres across and had an enormous volume.

And shortly after it was built, I met a friend of mine who said he didn’t notice the chandeliers. So I asked where he was standing, which was actually right below them, and he said that he was looking up all the time, but didn’t see the chandeliers.

At first, I wondered whether I should be insulted, but then I thought: this is the biggest compliment I could ever have, in a sense. Remaining anonymous and unnoticed, I think that’s a good start.

Blvd: When you collaborate with a brand like Flos, with its history and reputation for pushing boundaries, are you creating something that aligns with their DNA, or more from your own aesthetic?

Anastassiades: I grew up in Cyprus in a tiny place where there was no exposure to design whatsoever, and I had to seek my own path somehow in discovering that. There was one shop selling all the Italian brands, and I remember I used to love walking in there and looking at all these things. I didn’t know who created them, but I knew that they were beautiful. Flos was one of them, and I thought, ‘Wow. This is really a dream.’ So when my opportunity to work with Flos came about many years later, I felt that I have to honour that history.

And this is something that I tend to do with all the brands that I’m designing for, whether it’s furniture or whatever. I have to really understand and study their history and their DNA, and my contribution will be as unique as a conversation with them. If I were to explore a lighting idea for another brand, it wouldn’t be the same as the previous brand I worked for.

Blvd: Your work ranges from highly functional pieces to more whimsical ones, like the sculptural Miracle Chip discs. Lighting, too, has evolved beyond pure function into a more design-forward realm. How do you balance the functional aspects of design with the more expressive, design-driven elements?

Anastassiades: I always want to believe that there is some form of functionality in everything I do. And even if it is not obvious, it’s obvious to me that it serves a purpose. Whether it’s functionality in the conventional sense, or a different kind – an emotional functionality. And even those pieces, the sculptural discs you were referring to, they’re certainly abstract, but for me, they reflect light, you’re getting something out of it – there is an intention.

I think that the intention really is to trigger the imagination of the viewer in some way and engage with them. It’s a dialogue. You’re trying to have a conversation with your audience, whatever audience that is.

Left: ‘Arrangements’ round large and line light system. Right: ‘My Circuit Suspension’ in anodised warm grey and extruded calendered aluminium PMMA.

Blvd: Do you see yourself and your work as being rooted in a certain place or time? Do you see that audience being specific to a particular tribe?

Anastassiades: No, because you need to be able to speak to many people, and I really believe in democratic design. And although I produce some things that are unaffordable for many people – they’re made in very small quantities, they can be technologically challenging, engineered in an intricate way, take a lot of man-hours to put together, and all of that can escalate the cost – you can participate by viewing pieces, like when you go to a museum. You see an artwork and you don’t necessarily have to own it. I wish there were more places where you could actually view design in the same way you view art.

Blvd: Thinking specifically about lighting – which interacts uniquely with everything around it, and cannot be isolated as a discrete object – what is it like to design with such dynamic potential?

Anastassiades: Well, it’s a complex relationship, but at the same time, it shouldn’t be complex. It’s unique, by the fact that for 80 per cent of its life, it’s switched off, and just 20 per cent of its life is on – then all of a sudden, everything changes and something magical happens. You don’t view it purely as a sculpture or an object when it’s off, and when it’s on, it starts interacting with the space around it in a unique way.

The light itself and its illumination occupy or demand a different kind of space, they have a different interaction with the objects around them – not competing for the space physically, but in the sense of how the light starts casting shadows of the objects around it, as well as the shadows of its own form. So all these relationships fall into one thing, and I think this is the magic that comes with lighting.

Read next: