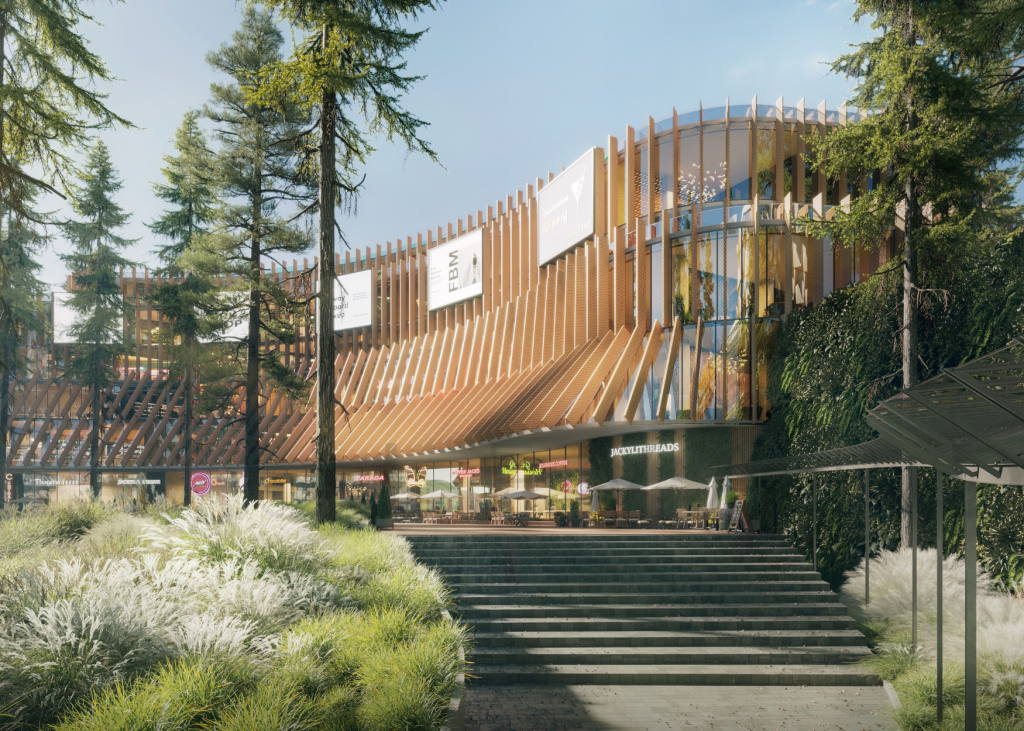

Overlooking the picturesque and crescent-shaped Xuan Huong Lake in Vietnam is Haus Da Lat, the country’s first ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance)-certified, ultra-luxury real estate complex. Spanning five hectares, the estate features Sky Villas, a luxurious five-star resort managed by InterContinental Hotels & Resorts, a wellness centre and Vietnam’s first ultra-private members’ club.

What sets Haus Da Lat apart from other ultra-luxury developments is the calibre of world-renowned experts behind its creative vision, most notably Kengo Kuma. Developed by The One Destination in collaboration with Terne Holdings and BTS Bernina Private Equity Fund, the project’s architecture is led by Kuma, one of Japan’s most respected contemporary architects and the founder of Kengo Kuma & Associates (KKAA), with interiors by the award-winning design firm 1508 London.

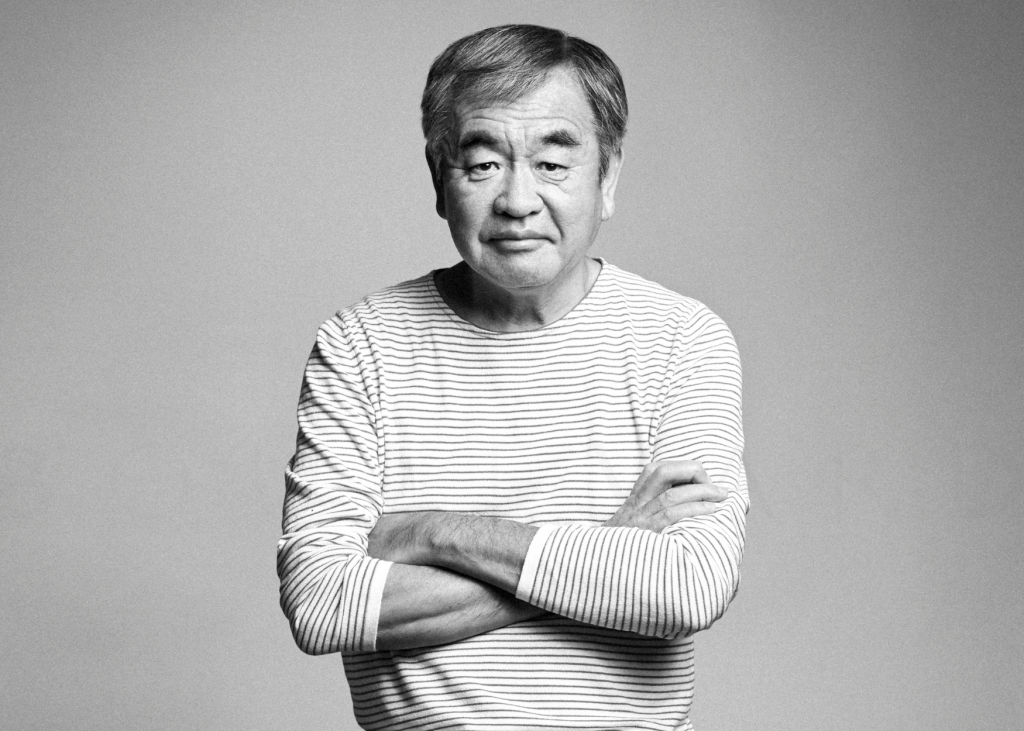

Kengo Kuma, founder of Kengo Kuma & Associates. Top: Artist’s impression of Haus Da Lat in Vietnam.

In an interview with Boulevard, Kengo Kuma emphasises his philosophy of “anti-object” architecture into the development’s design—a philosophy that transcends biophilic design, where architecture is only inspired or incorporates natural elements into buildings.

This ethos centres on “dissolving” buildings into nature, so that the structure feels at one with its environment rather than merely inspired by it. His approach prioritises seamless integration with the surrounding landscape through what he describes as “weak” architecture, using small, delicate and sustainable layers of wood, bamboo, ceramics and screens, instead of imposing concrete forms that appear unnatural.

“Everybody wants to connect with nature, but there’s a solid, heavy world that separates the relationship between nature and humans,” says Kuma. “I don’t want to be enclosed in a concrete box. I want to connect with and talk to the environment—and lightness and transparency of materials and design are the basis of that conversation.”

At Haus Da Lat, this approach is rooted in the site itself, defined by the region’s pine forests and terraced mountains. Kuma translated these natural cues through his signature blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics and modern, sustainable design, giving the project a distinct character compared with his previous works. This commitment to context also shapes his perspective on contemporary real estate development across the region.

“Developers are always asking me to create beautiful images for their pamphlets. I personally feel that a lot of developments going on in Vietnam are not respecting the location itself. Some are copying certain successful projects, and some are copying the gestures of certain famous architects,” he explains.

“With Haus Da Lat, we have developers who share our philosophy, which is to respect the place and not copy any other design, even our own.”

Kuma transformed these natural elements into geometric forms, a design language that runs throughout the development: “We created a space filled with geometry—one that has many corners and each one in the architecture creates dialogues with the environment. We worked very hard to create unique details on the terraces and balconies to maximise these corner situations.”

The balconies naturally open the architectural space with its surroundings, blending indoor and outdoor living seamlessly.

The balance between architecture and environment can also be found in the materials that Kuma used for Haus Da Lat. The main material used is pine wood, which merges seamlessly with the pine forest in terms of colour, texture and design.

Kuma also utilised the use of screens as doors into the design, which is a nod to traditional Vietnamese architecture. By filtering light, air and views rather than fully separating spaces, these screens create a subtle dialogue between indoor and outdoor living.

From wood to concrete, and back to wood

Kuma was born in Yokohama in 1954 and came of age during Japan’s postwar economic boom. During this period, he observed how many architects—particularly in Tokyo, a city once defined by wooden buildings—began turning to concrete and steel, gradually distancing architecture from the country’s long-standing culture of wood.

“The 20th century architects were playing the game of concrete and steel. It was mostly the only option available. But coming into the new age, architects including myself can have a bigger palette,” he says.

“Especially for us in KKAA, we try to adopt the local wood as much as possible. We don’t think this is the ultimate solution for sustainability, but it contributes to lessening the load for global warming.”

While Kuma acknowledges that it is impossible to completely avoid the use of concrete and steel in Haus Da Lat’s architecture, sustainability remains central to his approach.

“Concrete and steel are very anonymous materials. It is impossible to avoid them entirely, but we can combine them with local natural materials. At the same time, design should remain open to new technologies and engineering solutions,” he says.

Read next: