The interview: Leading Singapore architect Rene Tan of RT+Q

How football, music and humour shape Rene Tan’s counterintuitive approach to

architecture amid upheaval.

“The last thing I turn to for inspiration is architecture,” says Rene Tan. “I turn to music, or to football. If I hadn’t been an architect, I’d be a football historian. Football has taught me a lot of things – organising a team, organising space. There is an approach to football that emphasises what you do when you don’t have the ball – rather than what you do when you do have the ball. To mark space, to occupy and manage the space.”

Rene Tan and the architecture firm he founded with TK Quek, RT+Q, are renowned for their elegantly bold aesthetic that leans on simplicity even as it indulges in flashes of drama and wit. Tan himself, by contrast, is an effusion of ideas and talents, energies and tangents, which he seems barely able to contain let alone tie down to a discussion about architecture. But after a time and once we’re in sync, it starts to make sense — like marking space when you don’t have the ball.

“I went to college intending to be a musician — and thank goodness I didn’t continue in that direction – but I’m very influenced by my background in music,” he says. “And the biggest lesson I learnt: we were always taught never to overconduct the orchestra, to let the orchestra play by itself. So now when we come upon sites, I feel similarly that we shouldn’t overdesign, but rather be guided by what’s around us.”

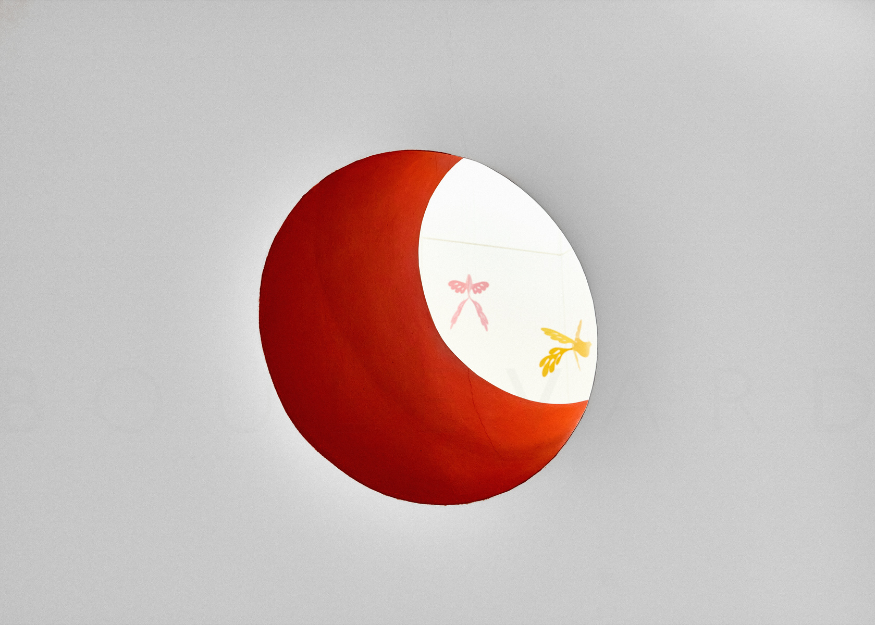

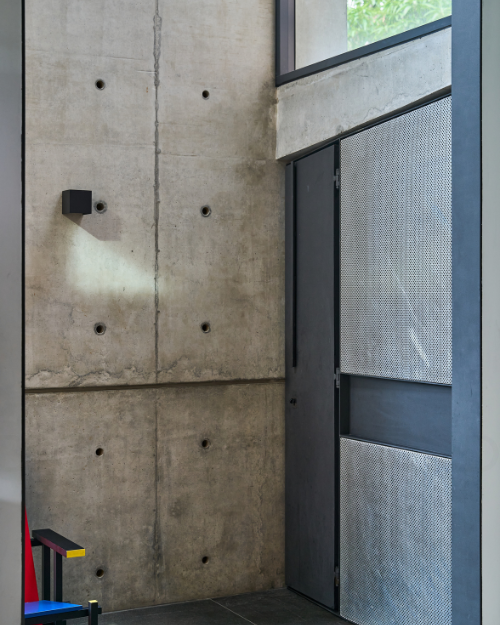

These gorgeous metaphors take shape in strong geometries, an apparent love of concrete, the slash of metallics – and then, where the site or the ball allows, a moment of daring or delight. At a Gallop Road bungalow, it’s all on show in the stunning basement gallery, where the achingly simple, white and rectilinear walls are shot through with a playful internal window painted in candy-apple red. At Petit Jervois, RT+Q’s recently completed and more recently awarded condo project for developer SC Global, it plays out in the simplicity of two cubes clad in glass and aluminium fins and juxtaposed against foundry-inspired rusted-metallic-looking porticos.

“One of the things that stands out for me at Petit Jervois is optimising, as opposed to maximising,” says Tan. “It’s not about how many units you can pack in, or how much architecture you can build. It’s about proportion, how much weight to put on, when it’s enough. And that’s a lesson I’ve learned from working with Simon Cheong.”

The exacting chairman and CEO of SC Global has commissioned RT+Q on projects spanning landed homes and condos and more than 10 years, and appears to have an affinity for the firm’s clean lines, materiality and striking modernity. But also, apparently, his own ideas about how the projects play out.

“Gone are the days of the great architect who just gave clients what he thought they should have. We try to do this but very often don’t succeed,” says Tan. “We have the most challenging time with Michelle Cheong [creative director at SC Global]. But we welcome challenging feedback and take it as an opportunity to launch us to the next idea, to discover something we might have missed. And it becomes a collaboration. It’s synergetic. Simon likewise – with his presence on site, his knowledge, commitment, desire, we learn from it.”

Tan, similarly, has a habit of visiting worksites, often roping in his team not only for the visit but also for the work: “The younger architects these days, no-one has laid a tile, no-one has plastered a wall – so I tell them to pick up the tools and get them involved.”

If nothing else, the team is versatile. RT+Q has delivered more than 100 landed houses, condos, offices, restaurants, the new =Dreams campus on Haig Road (above) — a residence for children from low-income households — along with a recent opera set. And lately, they’ve turned their hands to tombstones. “We don’t just design for opulence, or even just for the living. Design is design,” says Tan. So as our requirements and moreover our notion of the home undergoes massive upheaval, Tan’s approach is at once unchanged and remarkably apposite in its aversion to orthodoxy, training and even intuition.

“The key to thriving amid this upheaval is: don’t think like an architect. Training can inhibit our ideas, and we need to liberate our thinking, we need to design for flexibility and an unforeseeable future,” says Tan. “Luxury is freedom, and flexibility. The freedom to choose where and how we want to live. The flexibility to make it happen, and then to make it happen in a different way when our needs inevitably change.”

Tan’s own home cuts a fine figure in Watten Estate, with its trademark RT+Q off-form concrete, metallic statements and interposing greenery. It also exemplifies this flexibility in the ‘together-apart’ arrangement of spaces in which the family can gather or escape one another, such as the unusually large and light-filled wet kitchen, or his daughter’s secret music room hidden behind a bookshelf, or the glass panel on the floor of his wife’s double-volume ‘clothing chapel’ that offers a view of the living room, and any guests that may be waiting, below.

It also showcases another RT+Q signature: the luxury of delight. In the playful storage solutions and the moving walls, in the pops of colour against the warm woods and cool concretes, in the peephole windows between kitchens and also between master bath and bedroom, and especially in the copper-hued laundry chute that drops from the ceiling of the wet kitchen.

“We seem to have lost our sense of humour, but the elements of surprise and counter-intuition are important, the ability to engage our curiosity,” he says. “I think my house has a sense of humour. And I think that has to be the primary goal of architecture. To bring joy, and to provide for a better life.”